As a third-generation Minneapolitan, Kirsten Delegard grew up in the 1970s believing her hometown was a model city—that it was progressive and a leader in the fight for social justice. But after going away to college, training as a professional historian, and living in Europe and throughout the United States, she came back and saw it from a different perspective.

“I found myself confronting the fact that Minneapolis is a great place to be as a white person, and that it’s not a great place to be as a person of color,” she says. “Our racial disparities are, in many ways, the highest in the nation.”

Give to the Mapping Prejudice project

Delegard wanted to use her research skills to find out why.

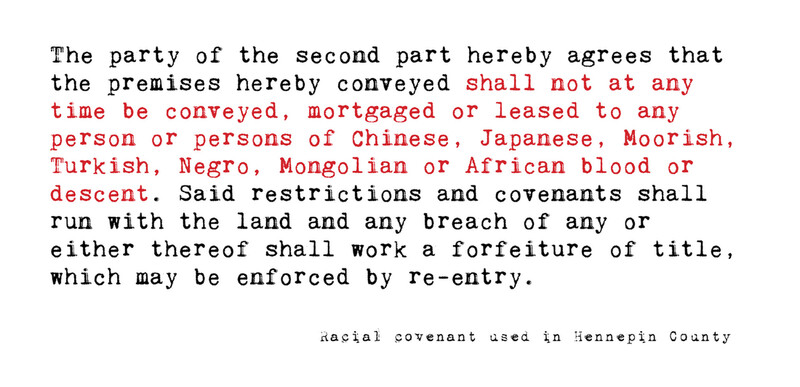

Her work studying the more troubling side of Minneapolis’ past for the Historyapolis project at Augsburg University often brought her to the University of Minnesota Libraries. As she sifted through documents in the archives and talked to people in the Jewish community and others, she kept hearing references to racially restrictive covenants—clauses in property deeds that make it illegal for a person who is not white to own or occupy a piece of land.

“But no one could tell me how many there were or what they said,” she says. “I became curious. Where were they? How did they get put in place? Who made decisions about where they went? How did they affect people’s lives?”

To find answers, Delegard partnered with Ryan Mattke, head of the University of Minnesota’s John R. Borchert Map Library; U of M graduate student and geographic information specialist Kevin Ehrman-Solberg; and researcher Penny Petersen to found Mapping Prejudice. Their goal: to search Minneapolis property deeds, build a database of those that contained racially restrictive covenants, and share what they learned with as many people as possible.

In 2016, they published the first-ever interactive map of a U.S. city showing how and where the use of racially restrictive covenants increased from 1910 to 1955.

Community comes together

Delegard, who now works for the University of Minnesota and runs Mapping Prejudice out of the Borchert Library, didn’t expect the attention the map brought once it became public. Team members have been interviewed by local, national, and even international media outlets and have spoken at conferences, U of M events, and neighborhood association meetings.

“I never anticipated the emotional reaction we got from people,” Delegard says. The first letter they received after the map was published was from a man who described how it altered his understanding of the community and made him want to work for change.

“The map has changed people’s lives,” she says. “That’s humbling.”

The publicity also brought volunteers and donors to the project. More than 4,600 people have contributed their time, including some 400 Medtronic employees who transcribed covenants from more than 5,200 property deeds into the database. After Minnesota’s stay-at-home order was issued in an effort to control COVID-19 and after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, the number of volunteers grew exponentially. The transcription rate went from a couple of hundred documents a day to more than 5,000 a day.

Donors also have been critical to the project’s success. Although the University provided space and the library’s resources, it didn’t cover staffing or other expenses. “We were always running on a shoestring,” Delegard says. “We only exist today because donors from the community sought us out and gave us money at critical times. Without that start-up money, we wouldn’t be here.”

Righting wrongs

That support for Mapping Prejudice has led to change in Minneapolis and throughout Minnesota. City leaders used its findings to inform them when developing Minneapolis’ 2040 strategic plan. “Data we produced provided a missing link to explain how the city’s land-use policies contributed to enormous racial disparities,” Delegard says.

Starting in the mid-1920s, when the city adopted its first zoning code, it became much more difficult to build anything but single-family homes in Minneapolis’s residential areas. That changed in January 2020, when the city began allowing buildings with up to three units to be built on any property, the idea being to create more affordable housing.

In 2019, Governor Tim Walz signed legislation that lets Minnesota homeowners amend their property deeds in order to “discharge” racial covenants. In other words, property owners can add language to the record saying they don’t endorse racial restrictions included in their property title.

Delegard says they’ve had hundreds of inquiries from people wanting to know how they can discharge restrictions.

In addition, the team, which finished its work in Hennepin County, began building a map for St. Paul and Ramsey County in January 2020. “Our goal from the beginning was to map racial covenants for Hennepin County, but it was clear as we approached the finish line that the work had just begun,” Delegard says.

She has received inquiries about creating similar maps in Milwaukee; Washington, D.C.; Syracuse, New York; Rochester, New York; Madison, Wisconsin; and Orange County, California. In 2020, the Mapping Prejudice team received a $324,478 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that will allow them to make the digital tools available to any community that wants to build such a map. In October, the project received a Catalyst award from the National States Geographic Information Council.

“It’s clear that this is bigger than us,” Delegard says. “We would not be able to win that grant without the help provided by our initial angel community investors.”