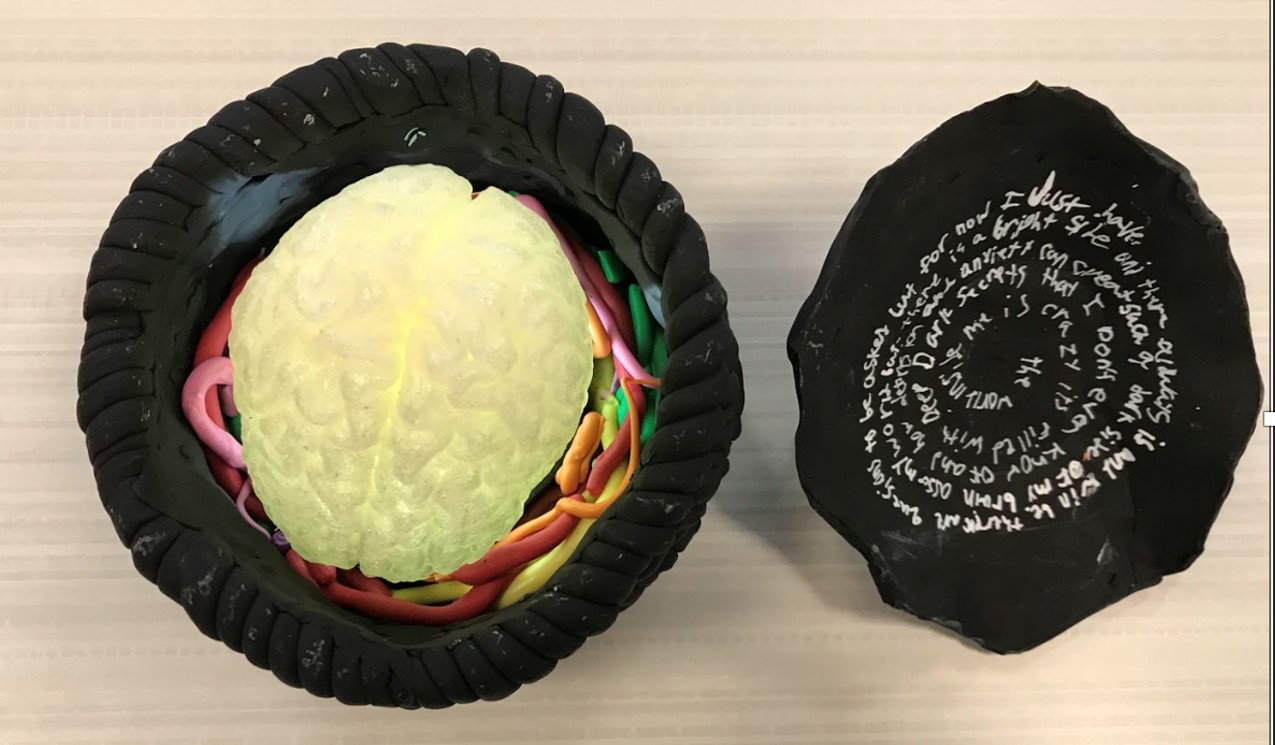

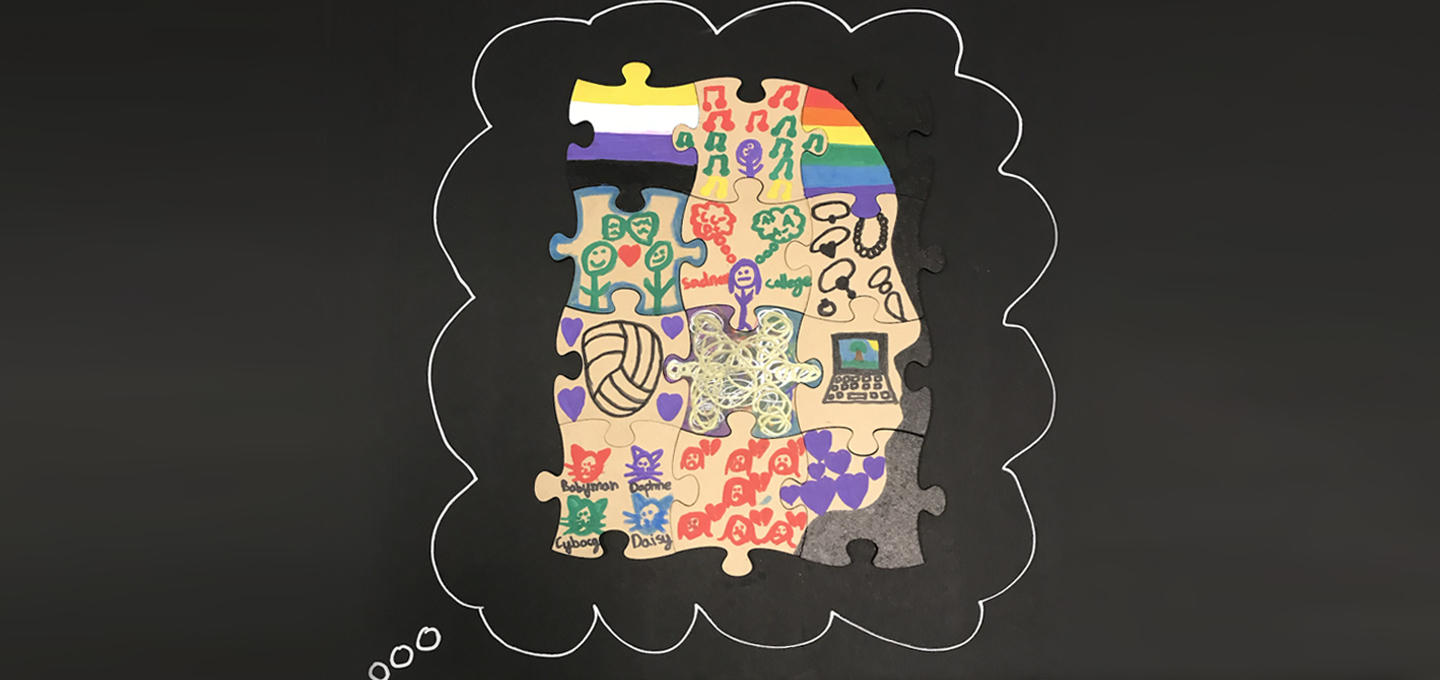

Creativity Camp participants made self-portraits out of personalized puzzle pieces. Photos courtesy of Kathryn Cullen

Last summer, groups of local youths would meet at the Masonic Institute for the Developing Brain (MIDB) to make self-portraits with personalized puzzle pieces, learn to contra dance, write letters to the Mississippi River, work with clay, and hike through the woods to gather materials to make a communal forest.

The kids, ages 12 to 17, all of whom had symptoms of depression, were participants in a two-week Creativity Camp that studied what happens in the brain when we engage in creative activities and whether those activities can affect depression.

“When they experience depression, adolescents get stuck in a rut with their thinking and emotions. They have a hard time shifting out of that,” says Kathryn Cullen, associate professor and head of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

Cullen noticed that young people who don’t respond to conventional treatments for depression tend to lose hope. “They need something to inspire them,” she says.

Teaming up

The inspiration for Creativity Camp came in 2018, when Cullen was introduced to Yuko Taniguchi. A writer, poet, and assistant professor for medicine and the arts at the University of Minnesota Rochester, Taniguchi had led an innovative art program for adolescents receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment at Mayo Clinic.

Cullen and Taniguchi teamed up to create a similar program in an outpatient treatment program for adolescents at the University of Minnesota. “This provided an opportunity for us to try out and develop some of our ideas,” Cullen says. They began to collaborate with colleagues from throughout the University (box). In these discussions, research questions emerged: What happens in the brain when we engage in the arts? How might those changes be helpful for depression?

With a Minnesota Futures Grant, Cullen and the team began putting together plans for Creativity Camp in the summer of 2022. Cullen says they got the idea for a camp from the College of Design’s Abimbola Asojo, who has been leading design-focused youth summer camps at the University for a number of years. “The idea of a camp makes it fun,” Cullen says. “It doesn’t sound like treatment.”

Starting in June, Cullen, Taniguchi, and team held three camps. Forty-three adolescents were enrolled, and 39 completed the camp. All had brain MRI scans before and after camp. In addition to measuring brain structure, the scanning sessions included measurement of brain function during rest and during a novel “Imagination task.”

Cullen and other members of the team including Bonnie Klimes-Dougan, Bryon Mueller, and Mark Fiecas, who have been doing fMRI research on brain development and depression in adolescents, will analyze the shape and complexity of the brain signals as a measure of the flexibility of neurocircuits. The team hopes the data will reveal new insights about how engaging in the arts can change the brain, possibly through increasing brain flexibility.

What have they learned?

Cullen says they’re now analyzing data they collected. So far, results are showing that after camp, depression symptoms are lower, and scores on measures of well-being are higher. Interviews with the adolescents and their parents supported this pattern. “There did seem to be an impact on depression and well-being before and after camp,” she says. “And it was clear that many of the participants loved the experience. They didn’t want it to end.”

Cullen initially thought that engaging in the creative process would be most helpful, but there was more. “It became clear that having the right setting and social environment really was important.”

Taniguchi says she was surprised by the sense of community that blossomed. “Some became good friends during the eight days,” she says of the participants.

One young person Cullen interviewed said the camp was a place where she didn’t feel alone. “She knew she was part of a group of kids who were struggling with their mental health and that she wasn’t going to be judged,” Cullen says. “Still, the program was a camp, not a therapy group, and the focus of the camp activities was on the arts, not on symptoms. That makes it more approachable and fun. The emphasis is on building strengths, and the impact on mental health is more indirect.”

Both she and Taniguchi found MIDB to be the perfect place to hold the camp. “It was wonderful to have a facility where we could do everything—the scanning, the cognitive assessments, the artwork,” Cullen says.

Most of the activities took place in the Annex conference room, which has large windows that made the kids feel like they were one with nature. “You’re allowed to think freely in that space, and they loved that,” Taniguchi says.

Imagining the future

Cullen, Taniguchi, and their team recently received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to launch a 10-year research program that focuses on understanding, measuring, and fostering creativity in adolescents through arts engagement. In September they launched the first stage of the project, “Imagination Central,” a year-long adolescent arts and science program at MIDB that is serving as a mini-laboratory to study the social, cognitive, and neural processes of creativity in adolescents.

Between and during arts activities, the research team is working with the adolescents to co-create a new and improved fMRI task that can measure creative thinking during a scan. The team plans to use the new tools in longitudinal studies to measure the impact of arts engagement on key outcomes that are critical for adolescents as they grow, develop, and become their “best selves.”